The Two-Way Exchange in Eliseo Pajaro’s Philippine Symphony

Photo of Eastman’s Graduate Class of 1953.

Eliseo Pajaro: second row from the top, fifth from the left

Source: University of Rochester Digital Collections

Setting the Scene

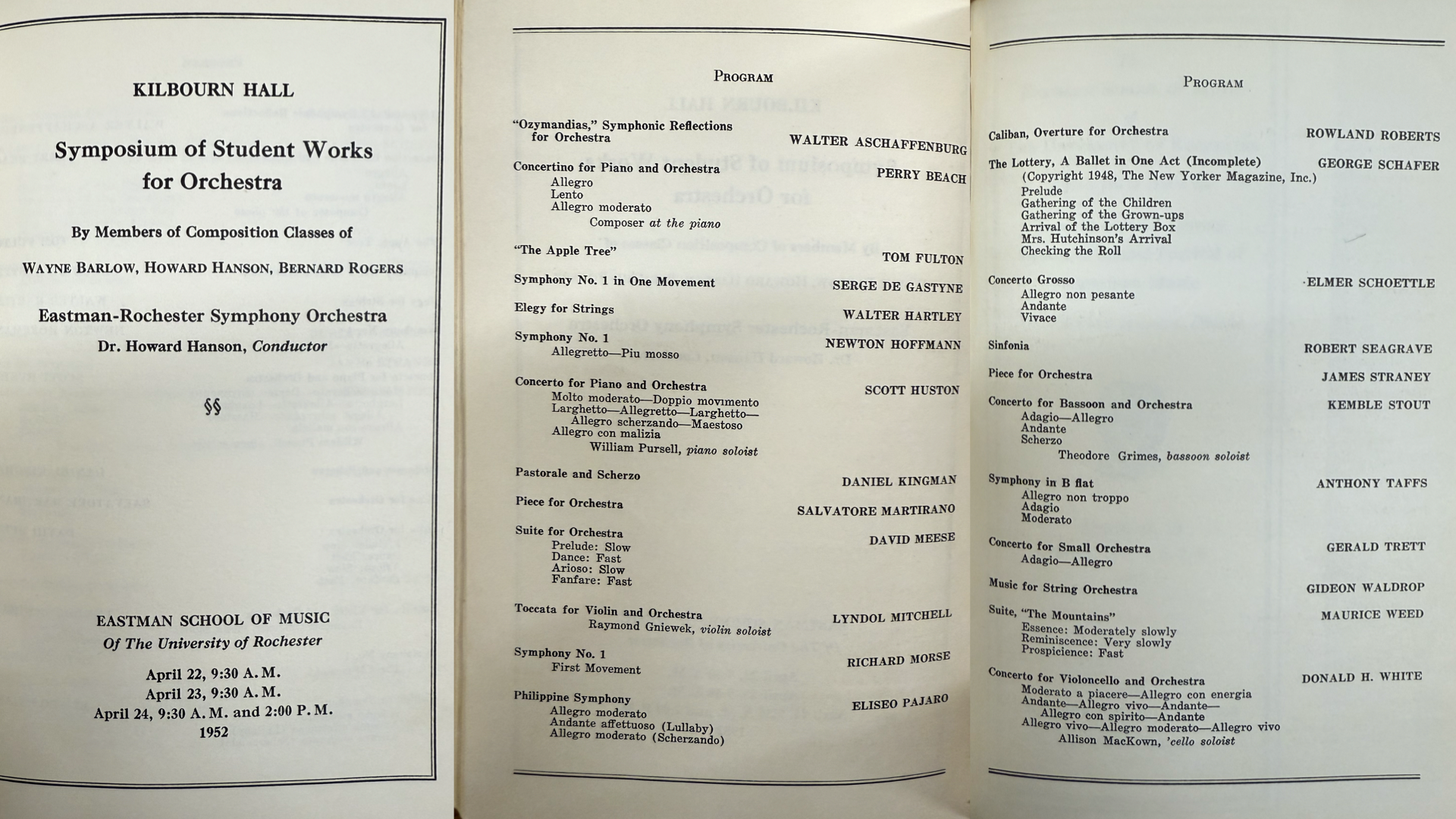

It’s April 1952. The Eastman-Rochester Symphony Orchestra, conducted by the school’s music director Howard Hanson, is gearing up for a marathon concert of student composers’ orchestral works. On the program are two new concertos for cello and bassoon, an elegy for strings, a concert overture, and—the Philippine Symphony by Eliseo Pajaro. The piece begins with a soft, mysterious cello and bass soli–the “dark” strings colors as his professor Bernard Rogers puts it. B-flat seems like the tonal center, but it’s difficult to parse out a mode. Our sense of time is also off-kilter, given the irregular 5/4 meter. Perhaps Pajaro was inspired by the “limping waltz” in Tchaikovsky’s “Pathetique” Symphony. Or maybe Pajaro wanted the listener to feel “lost,” as if we’re wandering in the dark and can’t quite find our sense of direction. Measure 9 puts us back in our place, for the whole orchestra joins forces and asserts the opening melody at a forte dynamic. Our sense of unity is maintained until the music climaxes at measure 24, after which the winds change direction with lyrical melody. The piece takes many twists and turns, but one thing is certain–Pajaro strives for extreme contrasts in harmony and orchestration.

Program for the premiere of Philippine Symphony.

Source: Sibley Music Library Special Collections.

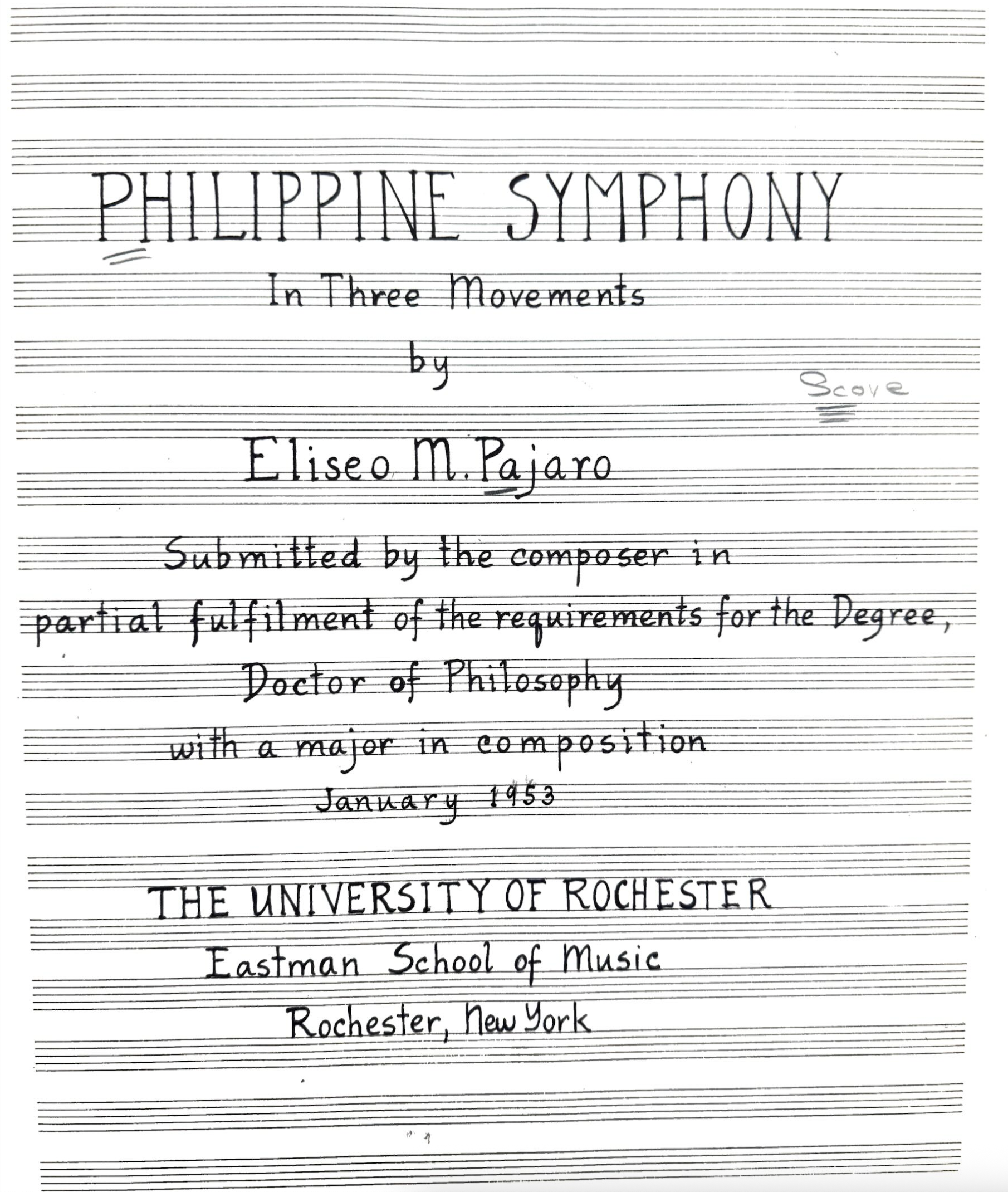

That year, Pajaro was finishing his PhD in composition at the Eastman School of Music, with this very symphony serving as his dissertation. He was set to graduate in January 1953 and return to the Philippines soon after, becoming one of the first Filipinos to graduate from Eastman. He then spent the rest of his career teaching music theory and composition at the University of the Philippines Conservatory of Music and conducting the Philippine National Symphony Orchestra while advocating for the study and creation of “serious music” in the Philippines. In 1955, he, along with ten other counterparts, founded the League of Philippine Composers and the Philippine Music Educators Group. The goal of the League was to write major works in Western forms like the symphony or opera while incorporating Filipino folk songs and instruments, whereas the Music Educators Group strived to “Filipinize teaching materials” through the incorporation of folk songs and dance in the public schools. He even won the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship in 1959 to compose his opera Binhi ng Kalayaan, which told the story of the Filipino nationalist José Rizal. To Pajaro, the role of a composer in the post-colonial Philippines was a serious matter. For one, the composer, through the writing of “quality” music in Western forms, contributed to the image of the Philippines as an advanced, forward-thinking society. On the other hand, Filipinos were grappling with their cultural identity after three centuries of Western colonization. The promotion of Filipino artistic practices, both on the stage and in the classrooms, was vital for national consciousness and pride.

Despite Pajaro’s impact on Filipino arts and culture, his musical legacy at Eastman and the United States at large is largely forgotten today. Using archival documents found in the Eastman Special Collections, as well as digitized newspapers from the United States and the Philippines, I construct a narrative of Pajaro’s early career as a means to circumvent institutional amnesia. Concert programs, original score manuscripts, and historicized newspapers point towards a two-way exchange between Pajaro and Eastman; although he was here to study composition and orchestration with Howard Hanson, Bernard Rogers, and Wayne Barlow, he was also here to introduce Americans to Filipino music and culture. I argue that Pajaro began to fulfill his proclaimed role as a composer in the “New Society” at Eastman, well before the height of his career.

I first provide a brief history of the American-colonial and post-colonial Philippines to better understand the place of Western arts and education in the early 20th century. I then explore how the synthesis of Western and Filipino art music served as a means towards developing a national identity and how Pajaro’s early career—from before Eastman to his doctoral graduation—aided in those developments. I then hone in on the first movement of the Philippine Symphony by analyzing the interconnections of form, harmony and orchestration. Following music theorist Roger Grant, I believe music analysis “can help us to reimagine the social relationships, routines, and power dynamics that animated [Filipino orchestral music].” Specifically, analysis within this context serves three purposes: 1.) to the compositional language Pajaro was working with at that time; 2.) to help empathize with Pajaro and other 20th-century Filipino composers who valued prowess in Western music traditions as a way to attain higher social and/or economic status; 3.) to view the orchestra and its corresponding genres as symbolic of cultural identity. To my knowledge, there are no publicly-available recordings of the piece. Therefore, I construct MIDI recordings using digital notation software and digital audio workstation Logic to aid my analyses. Pajaro’s original manuscript served as my guide throughout the transcription process, and I do my best to remain faithful to the score.

There is one glaring omission from my analysis: the Filipino elements used in this symphony. In an interview with Pajaro, Howard Hanson asks him to explain the Filipino folk songs in the Philippine Symphony. However, the interview transcript, found in the Special Collections, only contains Hanson’s part. Likely, this document was Hanson’s script, for this interview was being recorded for a radio broadcast. Despite my best efforts, I have been unable to identify which folk songs were used in his symphony. There is no secondary literature on the piece, and I have been unable to find any semblance of program notes in the archives. This is an area of further research I would like to pursue, and I would appreciate any leads. However, the lack of primary or secondary surrounding this work only exemplifies said institutional amnesia. It is my hope that this project sparks further discussion of Eliseo Pajaro’s music and his legacy.

As you read, consider listening to this YouTube playlist of some of Pajaro’s other pieces.

Contextual Information

American Education and National Identity

For nearly four centuries, the Philippines was colonized by Western countries; Spain conquered the islands from 1565-1898 and the United States conquered from 1899-1946. Under the guise of “benevolent assimilation” ordered by President William McKinley, the United States established American-style government, communication infrastructures (newspapers, telephones, radio), schools, and more during the early 20th century. The public school system was particularly robust; between 1903 and 1940, the number of schools increased from 3,000 to 13,000. These schools enforced English-language instruction and communication as well as American history, traditions, democratic principles in order to paint an idealistic picture of the United States. State-sponsored universities and conservatories were established as well; St. Scholastica's College and the University of the Philippines Conservatory of Music (hereafter UP Conservatory), were established in 1906 and 1916, respectively. Prior to American rule, the musical landscape was largely tied to the Roman Catholic Church. Filipino musicians typically received their training from the clergy, and produced vespers, hymns, and masses to be performed in liturgical services. Formal music schools established by the United States created both a burgeoning secular music scene and a class of highly-trained musicians adept at composing and performing Western music. The UP Conservatory in particular produced Nicanor Abelardo, Francisco Santiago, Lucrecia Kasilag, and Eliseo Pajaro, all of whom led successful careers in the Philippines and abroad. The music schools taught Western music theory and history, training composers to write in genres such as the symphony, concert overtures or symphonic poem. Composing for the orchestra was seen as a respectable endeavor given its technical and lengthy nature.

UP Conservatory of Music, 1916

Source: University of the Philippines College of Music Website

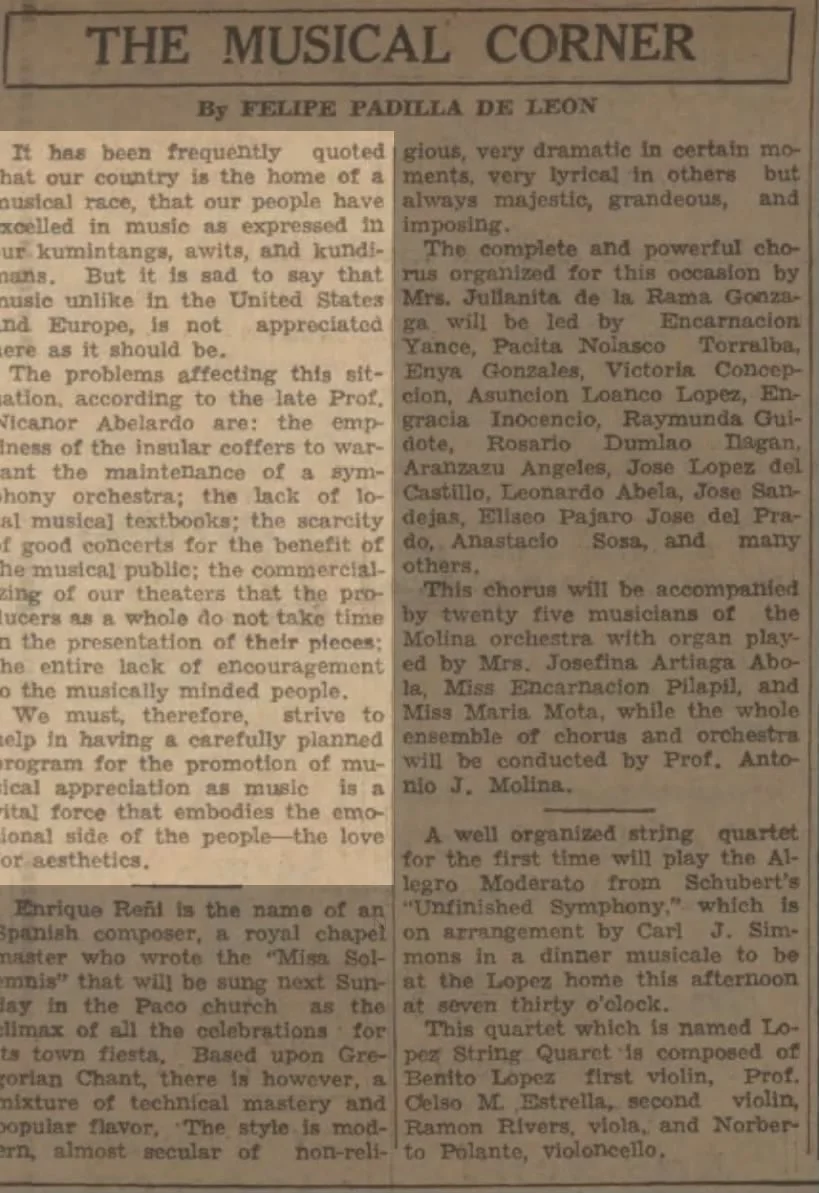

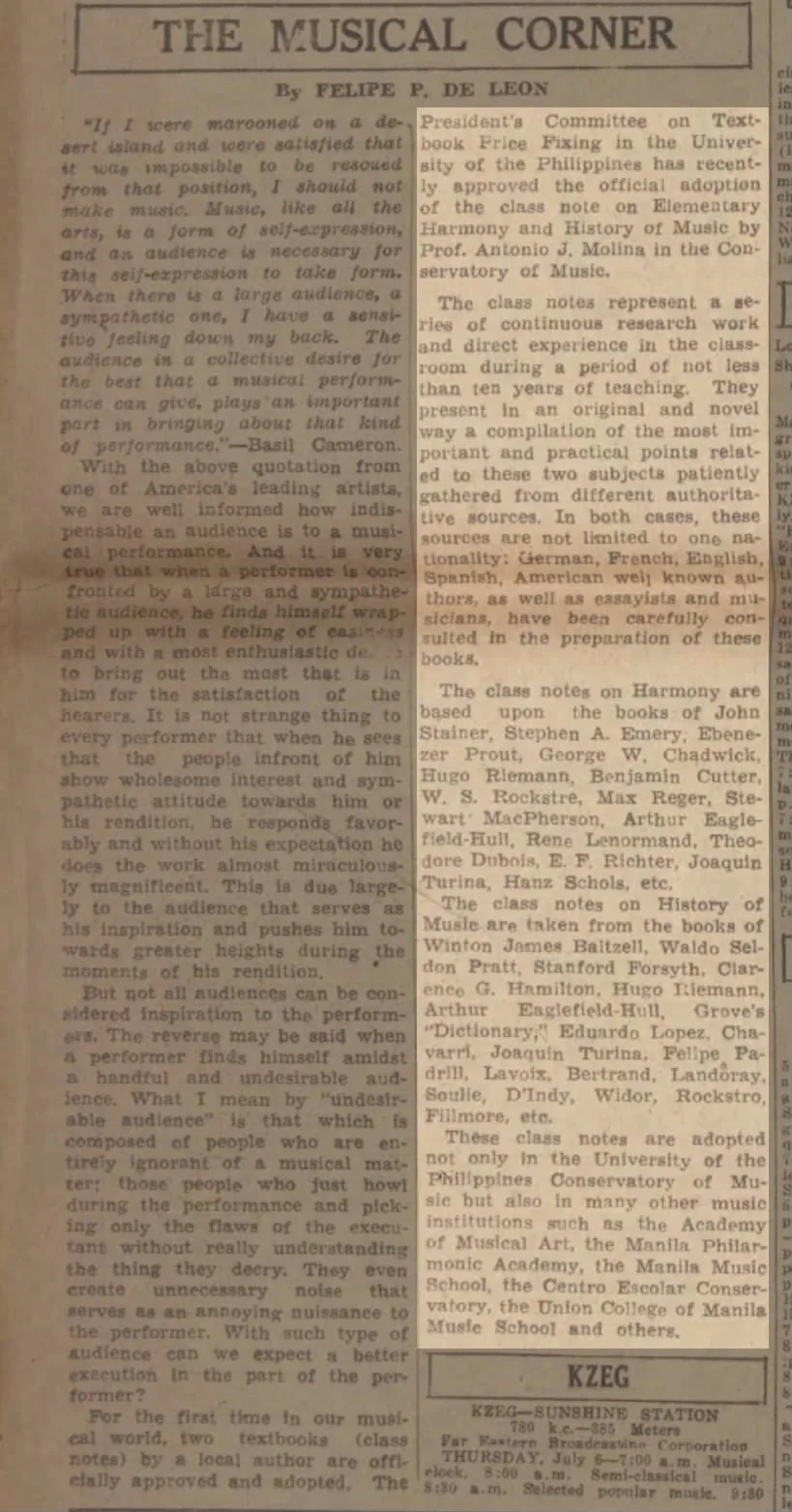

Views on the American school system were mixed. Some Filipinos feared that English-language schools would create a “homogenous” country with forgotten cultural values. Sociologist Anthony Christian Ocampo described the "benevolent assimilation" behind the new education system as a euphemism for "paternalistic racism," for they did not consider the needs of the Filipino people. Others viewed the school system as positive, for their English-language studies allowed them to work in the government and attend school abroad. The music schools in particular also sought to position Western aesthetic ideals as being technologically superior and more sophisticated. The American government hired foreign professionals to serve as the first teachers at the UP Conservatory with the goal of “rais[ing] the creative skills of the Filipino composers to the same level as composers from the Western world.” This, of course, relies on the problematic assumption that Filipino music was somehow inferior prior to Western intervention. Local news outlets lamented the “lack of music appreciation” in the Philippines compared to the United States and Europe, and cited the absence of a systematic study of music as the cause. Just 23 years after the founding of the UP Conservatory, the first music textbook written by a Filipino author (Antonio J. Molina) was published and distributed to music institutions across the country. Notably, only European and American sources were referenced in the textbook, further cementing the notion of Western art music as the authoritative source for musical ideals.

The Tribune, Manila, Philippines, August 20, 1936, newspapers.com

The Tribune, Manila, Philippines, July 6, 1939, newspapers.com

The American government also established the Pensionado Act in 1903, which allowed Filipinos to pursue higher education in the United States, under the condition that they would return to the Philippines immediately after graduation to become civil servants. As more Filipinos were being educated abroad, the desire for a national identity, apart from the Americans, increased. The arts and humanities proved to be a valuable tool for this endeavor. The University of the Philippines formed an “oriental languages” department in 1924 as interest in Filipino regional languages grew. UP Conservatory professor Francisca Reyes traveled throughout the Philippines to record regional folk dances, eventually leading to their popularity in Manila and the establishment of a canon of national dances. When composer and pianist Francisco Santiago performed one of his own works at a solo recital in Chicago in 1924, he stated that his reasons for doing so were that “Filipino above all, I thought I should do my part [for] propaganda for our country. I wanted the American public to perceive that we are not savages.” Later, Santiago became the first Filipino director of the UP Conservatory and encouraged the study of indigenous Filipino music at the institution.

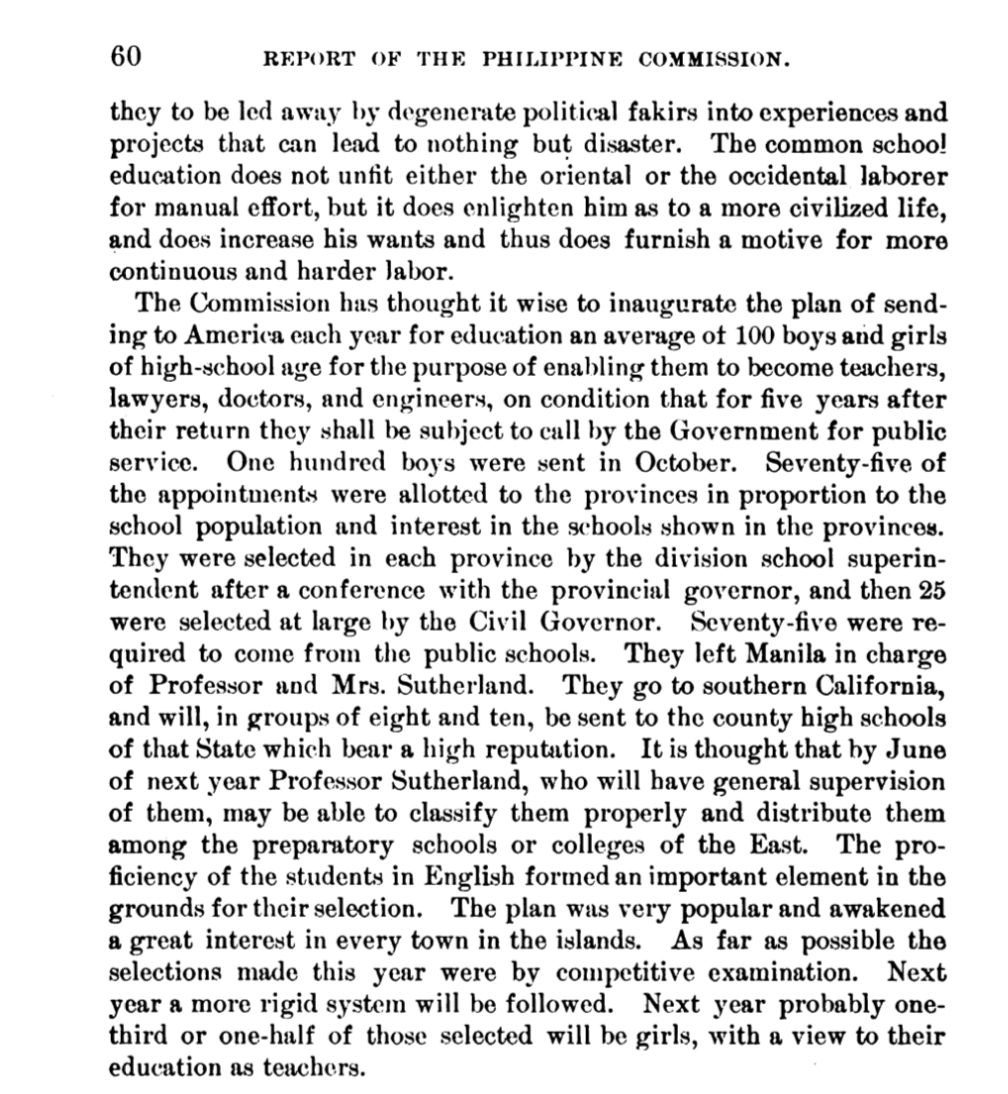

Report of the Philippine Commission to the Secretary of War 1902/1903, part 1

Source: Haithi Trust

The goal, though, was not to abandon Western music training and resort to “just” the study of indigenous music. The nationalist Filipino works that grew out of the American colonial period blended Filipino music into Western classical forms. This was partly to preserve Filipino folk songs, which were seen as becoming lost without their notation. At the same time, Filipino musicians were looking for ways to construct concrete symbols of “Filipino-ness” that would gain respect in the global community. Nicanor Abelardo, a student and later a faculty member at the Conservatory, wrote:

~Nicanor Abelardo

It was also at the UP Conservatory that Pajaro decided he wanted to pursue composition as a career. The encouragement to do so came from none other than Francisco Santiago, who by that time was the conservatory’s director. Santiago’s sentiments clearly made an impression on Pajaro, since most of his compositions from then onwards were based on Filipino folk songs or mythology. Pajaro’s documented works written pre-Eastman include the symphonic poems Cry of Balintawak Overture (1947) and The Oblation (1949), which refer to the start of the Philippine Revolution and an offering to God, respectively. Both pieces could be considered nationalist works given their subject matters, though it’s impossible to determine the level of hybridization with Western aesthetics without the scores, both of which are assumed to be lost.

It should be noted that the composers most often recognized for formulating a national music identity (Francisco Santiago, Nicanor Abelardo, Antonino Buenaventura, and later Pajaro and Lucrecia Kasilag) were all graduates and faculty members of the UP Conservatory. Who, then, decided what “nationalist music” was? Was it the people, or the University of the Philippines? Was the hybrid of Western and indigenous music popular among the majority of Filipinos, or only those trained at the Conservatory? Answers to these questions are beyond the scope of this article, however, I mention these questions to be mindful of the histories that are told about Filipino music. One university tells the narrative of American-colonial Filipino music, even though they were far from being the only site for music making.

Interlude: Pajaro’s Early Life

Not much is known about Pajaro’s life prior to his music career; most of the publicly available biographical information lists his birth and death dates/locations and the most notable aspects of his career, like his professorships and the Guggenheim Fellowship. To my knowledge, the only detailed account of his biography comes from Helen F. Samson’s book, Contemporary Filipino Composers: Biographical Interviews. Even with this limited information, it is still possible to get a sense of his musical training and early career prior to Eastman.

Eliseo Pajaro was born in Badoc, Ilocos Norte in 1915, 445 kilometers north of Manila. His early musical training was given by Issac Roflox, who at the time was a retired member of the Philippine Constabulary Band. Rapidly progressing through the solfeggio lesson books, his teacher gave him a clarinet and he soon became the youngest member of the town band. At age nine, he began his studies with Marcial Wasan who also encouraged him to play in his jazz orchestra. By high school, Pajaro was performing with the Modernista Band in Laog, the most popular jazz band in Ilocos Norte, as well as for zarzuelas, staged musical works which “served as a medium of political protest and criticism of colonial rule.” Pajaro finished high school in 1932 and went on to study at the UP Conservatory until 1941 amid the outbreak of World War II.

Badoc, Ilocos Norte to Manila

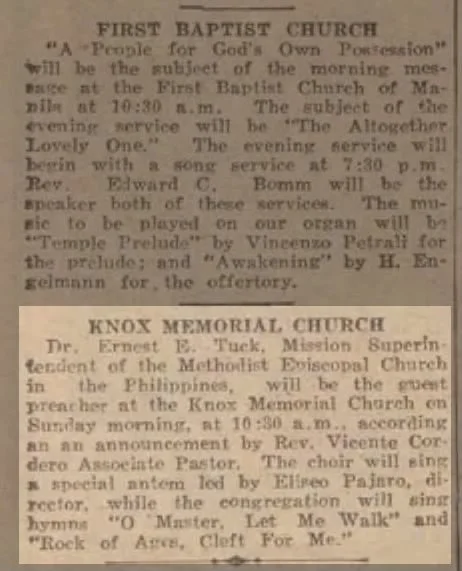

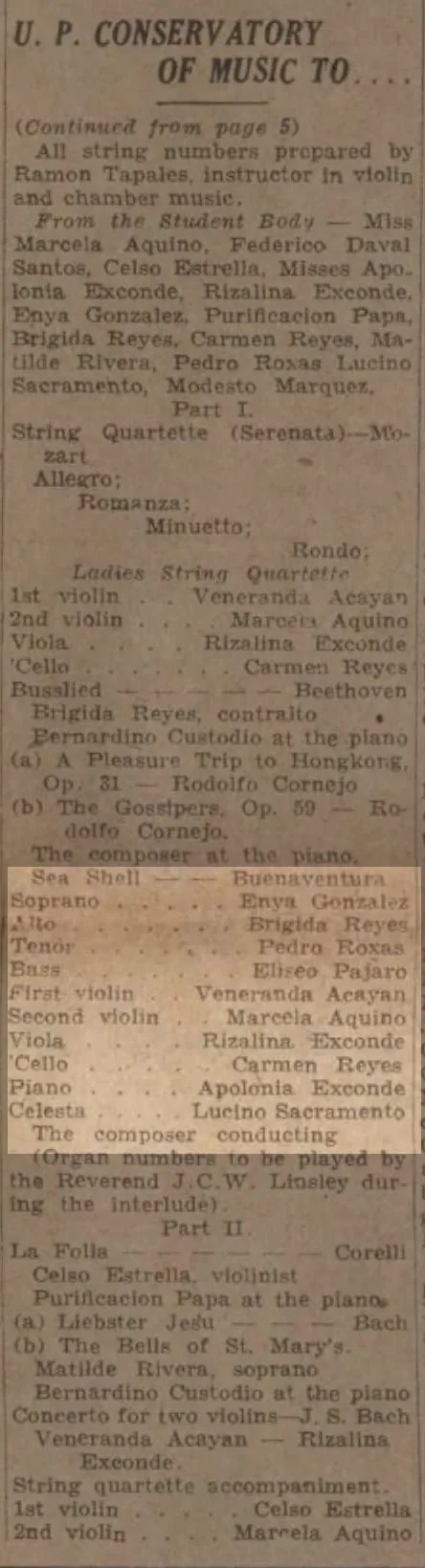

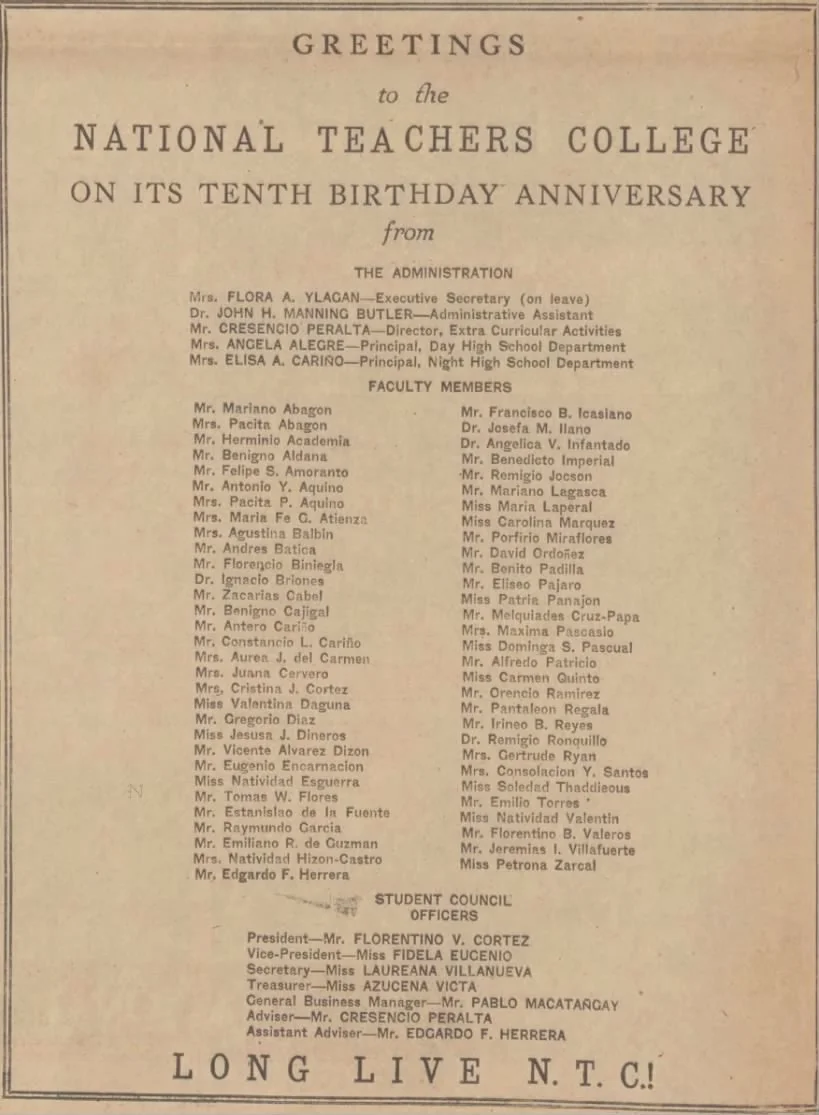

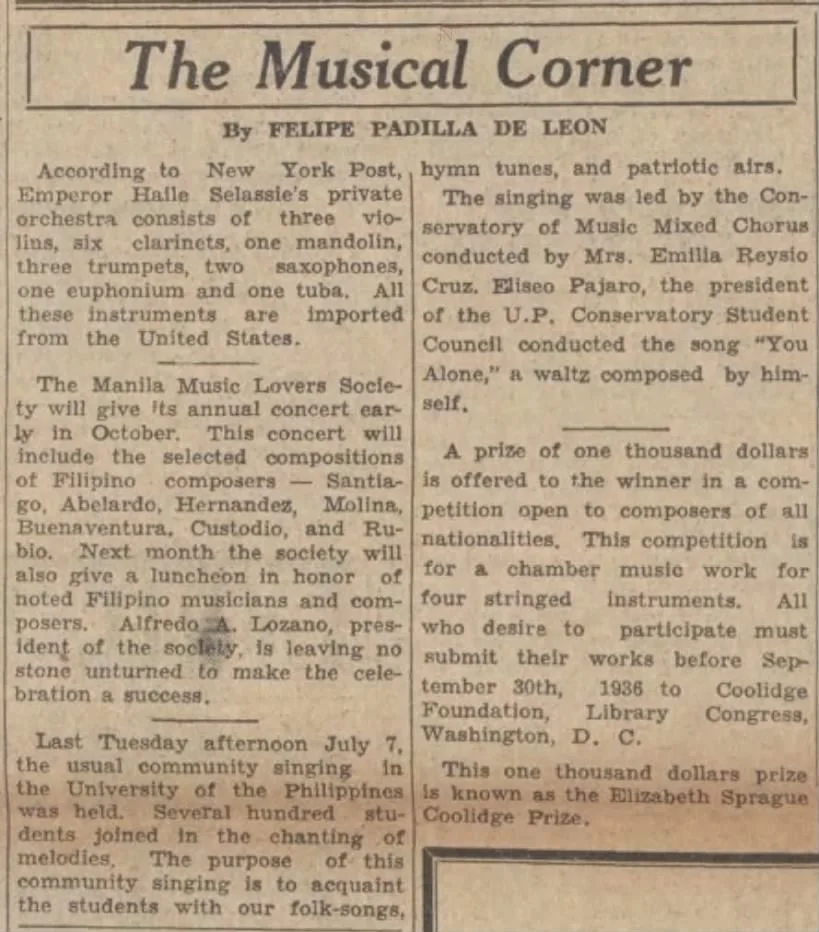

Newspaper clippings from Manila’s The Tribune showed Pajaro’s endeavors turn towards choral music—singing, conducting, and teaching it—while at the UP Conservatory. He sang bass in and conducted the conservatory choir, leading events that taught Filipino folk songs to the public as well as introducing Filipino classical music to new audiences, an endeavor that potentially previewed his career down the line. Pajaro was also a devout Christian and thus served as music director at the Knox Memorial Church, who later helped him secure a scholarship to study in the United States. Starting in 1939, he was teaching music methods and choir at the National Teacher’s College while simultaneously attending to his studies, proving to be fruitful for his teaching duties at Eastman and later professorship at the UP Conservatory.

The Tribune, Manila, Philippines, November 28, 1937, newspapers.com

The Tribune, Manila, Philippines, November 11, 1933, newspapers.com

Formal Structure

The Tribune, Manila, Philippines, September 29, 1939, newspapers.com

Philippine Symphony: A Closer Look

The Tribune, Manila, Philippines, July 16, 1936, newspapers.com

Given that the UP Conservatory during Pajaro’s time of study valued the hybridization of Western music with indigenous Filipino music, how was he able to imbue Filipino musical aesthetics to his colleagues at Eastman while simultaneously developing his own musical voice? The answer can be found in his doctoral dissertation, Philippine Symphony. Completed after three years of study and one completed degree from Eastman, the Philippine Symphony stands at the edge of tradition. The harmonies are grounded in tonality, steering clear of the atonal or serialist techniques popular at the time. And yet, they are used in non-functional and ambiguous ways. A single antecedent might pass through two unrelated triads or a chorale-like gesture might be paired with a bassline in a different key. The form follows traditional structures from the Classical and Romantic eras, but does so in an obscure way. The orchestration, on the other hand, seems to abide by Bernard Rogers’s teachings the most. Rogers was on the composition faculty at Eastman from 1930-1967 and published the book The Art of Orchestration: Principles Tone Color in Modern Scoring in 1951. This book is the result of decades of experience composing and teaching, and likely made its way into Pajaro’s lessons. Pajaro’s symphony was also conducted by Howard Hanson, who probably offered his suggestions on orchestration during the workshopping phase. The “giving” of traditional yet unconventional harmonies and forms, and the “taking” of orchestration principles, forged the two-way exchange between him and Eastman, allowing Pajaro to realize his goal of creating “serious music” that reflects national pride.

Let us return to the first reading session of Pajaro’s Philippine Symphony. As the musicians are reading through their parts, they realize that they need not consider the pitches as pulling towards one particular tonic, but rather as a way of creating harmonic ambiguity. Take the opening solo, for example. The celli and basses first outline a B-flat major triad in first inversion, but then drop down to a B natural and then up a perfect fourth to E, outlining the fifth and root of an E chord; two chords that are a tri-tone apart. The second violins and violas join the celli with a chorale-like accompaniment. Their first three chords pull us back towards the “flat” keys, but gets quickly interrupted as the four string sections join together to form a C Major 7 chord; where does that fit into B-flat major? Their accompaniment is supporting the first violins who are playing an undulating figure that then gets passed to the flute. The first violin/flute figure may look like mere transition material, but it actually serves as an important motive for the rest of the movement. I call it a “countermelody,” even though it’s not working as counterpoint in this first iteration.

Score follower to the exposition of Eliseo Pajaro’s Philippine Symphony. This video was created by engraving the original manuscript, found in the Sibley Special Collections, into digital notation software. All timestamps in the analysis are in reference to this video.

Even within the first six measures, it’s clear that the musicians need to get used to unrelated triads and distant tonicizations. The harmony becomes more ambiguous starting at m. 13 [0:18], as the violins and woodwinds begin a linear ascent towards a cadence at m. 24 [0:28]. As the strings and woodwinds play a chromatic sequence up to a high F#, the celli and basses play an augmented version of the countermelody over the course of five bars. The horns join in on the countermelody, too, but are inverted; they follow the same intervallic sequence as the celli and basses but with the opposite contour. The big cadence that greets the musicians at m. 24 does not outline a triad at all; rather, it’s a large quintal chord spanning over three octaves, with A in the bass and F# in the soprano, filled in with E and B throughout the inner voices.

Just as the musicians are getting used to the ambiguous harmonies, they are suddenly met with a new theme, with the mood suddenly changing from dark and intense to sunny and lyrical. To those accustomed to classical formal structures, a half cadence followed by a textural gap is expected in between the two contrasting themes, as a sort of rhetorical pause. This creates what’s called a medial caesura (MC), a defining feature of two-part expositions (expositions with a primary and secondary theme). In eighteenth-century sonata expositions, MCs typically involved a break in sound or a noticeable decrease in energy, preparing the onset of the new theme. In the Philippine Symphony, however, the woodwinds elide into the tailend grand quintal cadence [0:29] to start a new theme. The elision is supported by the celli and basses, who end their descending bassline at the start of m. 26, rather than cutting off with the rest of the orchestra at m. 25. One could argue that the lack of a clearly-defined MC would make this a continuous exposition. However, continuous expositions are typically characterized by a “spinning out” or varied restatements of the primary theme. If you listen to the two themes at [0:00] and [0:29], though, it is clear that they are contrasting, given the meter and underlying harmonies. I propose that Pajaro separates the two themes with an obscured medial caesura, which the theorist Mark Richards defines as an “unusual treatment of either harmony or texture.” In Pajaro’s case, the MC is obscured because the cadence at m. 24 ends on a quintal chord, rather than a half cadence. Additionally, the accompaniment in the cello and bass extend into m. 26 after the secondary theme has already started. Richards would call this a doubly-obscured medial caesura, since two independent elements of a typical MC are obscured.

The secondary theme area spans longer than the first, lasting for 30 instead of 12 measures (mm. 26-56 or 0:29-0:57). This section is characterized by antiphonal contrast between the woodwinds and strings, tonicizing a new key area with every new iteration of phrase (see video example below). The period phrase structures work well for the antiphonal contrast; in some instances one instrument might take on the antecedent whereas another one, from either the same or different instrument family, would take on the consequent. An example of this is from mm. 26-34 [0:29-0:36]. Here, the flute begins the phrase with a lyrical melody that straddles between G Major and E minor; while the first two notes outline a strong ^5-^1 in G Major, the next measure of the phrase ^6-^3, or ^5-^1 in E minor. The flute ends the antecedent on a B-flat unexpectedly, allowing the clarinet to finish the phrase with a consequent in B-flat minor. The violins immediately follow the clarinet with a reiteration of the antecedent in G# minor, adding rhythmic variation with dotted quarter and eighth notes. However, G# minor is quickly thwarted by the flute, as if it were never supposed to have happened; the flute ends the phrase with a consequent that fits a little more squarely into E minor, outlining ^5-^1 over in E minor over four measures. The tonicization progression of G Major/E Minor, B-flat minor, G# minor, and back to E minor occurs once more as the woodwinds and strings repeat the melody with the same call-and-response pattern. Pajaro creates variety by building on the orchestration and texture. For example, whereas only the first violins played the melody from mm. 34-37 [0:34-0:39], the second violins joined in from mm. 42-45 [0:43-0:50], adding “power” by supporting the first violins an octave lower. The woodwinds and brass also support the strings in that same section, whereas in the previous strings melody they were alone. Here, the woodwinds and brass, along with the violas and cellos, play a pulsating accompaniment as opposed to simple, sustained chords. This adds both rhythmic and textural variety.

Video demonstration of antiphonal contrast in the secondary theme.

Two sections are elided into each other once again, as the bassoon and celli begin the transition to the final section with a long stepwise ascent, as the upper strings and woodwinds end their final phrase of the secondary theme. Harmonically, this section remains within familiar key areas, cycling through E minor/G Major, A minor, and finally C# minor, relating back to the G# minor tonicization in the secondary theme. Even with familiar keys, the energy is relentless. For one, the ascending sequence continues from m. 54 all the way to m. 83 [0:55-1:20]. The bass instruments are not solely responsible for the ascent, either. The bassoon and celli end their ascent on G4 at m. 59 [0:58], leaving room for the first violins to pick up on a B-flat in m. 64 [1:02]. Alongside the first violins is the rest of the strings as well as the brass and bassoon playing an incessant dotted rhythmic pattern in unison. This figure occurs repeatedly throughout the rest of the exposition, so for clarity’s sake, I will call this figure the “X motive” hereafter. The oboe then joins the ascent by responding to the first violins a half step higher on B-natural before continuing with the ascent with their own stepwise sequence. The upper strings join the oboe at the unison in m. 70 [1:08], playing spiccato eighth notes to add textural variety. The ascent finally ends at m. 83 on an E6, almost three octaves above the start.

By m. 80, the entire orchestra joins in on the X motive, hammering it repeatedly until m. 88, at which point there’s a grand pause [1:17-1:24]. This is the first time a true break in sound occurs that can be said to divide the exposition into multiple sections. Is this the “real” medial caesura? Remember from earlier that MCs are typically composed of a half cadence followed by a textural gap, most commonly a break in sound. M. 88 lands on a C# minor chord, which is a departure from the E minor/A minor key areas from the transition. Additionally, the C# minor chord is over an F#, and the G# is in the bass of the chord, rather than the root. So even if the piece had modulated into C# minor, the cadence does not make that clear; there’s no firm chordal root to ground the harmony. While this is not a half cadence in the literal sense, it does set up the expectation for new material; the piece does not sound “done.” Both harmonically and texturally, this grand pause sounds more like a “true” MC than the one at m. 24. But MCs are what differentiate the primary theme from the secondary theme; why is there another one so late in the exposition? In this case, Pajaro is creating a double medial caesura. For Hepokoski and Darcy, a second medial caesura might occur after the secondary theme as a means to extend its thematic material and evade the essential expositional closure, the strong perfect authentic cadence that typically ends the secondary theme. In the case of the Philippine Symphony, the increase in energy, culminating in the blows from mm. 80-88 leads the listener to believe that a strong closing theme will occur. Instead, the material after the second MC restates and varies material from earlier in the exposition, creating ambiguity as to whether or not it forms a closing section or extends the secondary theme [1:24-1:56]. It begins with a stately horn and trumpet duet, performing what sounds like an augmentation of the secondary theme. The secondary theme restatement is interrupted in m. 93 [1:28] with a new ending tacked onto the end of the phrase, based on the countermelody from the opening of the piece. The secondary theme augmentation and new ending form the basis for the rest of the coda, as instrument families play one or the other in blocks of sound. The exposition finally ends with an E minor/G Major cadence played by the entire orchestra, giving a feeling of triumph after an exposition filled with ambiguous tonalities and frequent character changes.

Watch this video to synthesize the above analysis and listen to the exposition once more.

Form as Orchestration, Orchestration as Form

In his book The Art of Orchestration: Principles of Tone in Modern Scoring, Bernard Rogers writes:

“Orchestration is the servant of form. Its function is to illuminate and strengthen tonal structure. It is the clarifying agent, bringing into relief the salient patterns and details, revealing structure at its vital points… A change of instrumental color helps to define a new theme, phrase, or section. This principle of contrast is basic in the tonal scheme. It may be carried out through alternation of choirs (antiphony), by change of solo instruments, or through counterpoints assigned to new colors.”

~Bernard Rogers

As was just discussed, the form of the exposition follows principles of sonata form but with two medial caesuras. What methods did Pajaro use to clarify the exposition’s structure to the performer and listener? It certainly was not harmony. Rather, Pajaro used an auditory perception phenomenon, created through orchestration techniques, called timbral emergence. Timbral emergence is defined by Stephen McAdams, Meghan Goodchild, and Kit Soden as the fusion of instruments to create a newly synthesized timbre. This phenomenon works best when two or more instruments are in rhythmic and/or intervallic unity, for the streams of sounds are more likely to blend together. Pajaro created instances of timbral emergence by creating “blocks” of sound, in which a group of instruments would play in unison. Pajaro also layered two or more of these blocks together to create multiple melodic streams. The texture never got too busy, though, for the groups of instruments would blend together to create cohesive units. One clear example of this is when the full orchestra expands the sound of the opening cello/bass solo from mm. 9-12, playing in complete pitch and rhythmic unison. Rogers describes string unison doublings as having a “full, robust effect” with “great power and intensity.” This sudden expansion in sound signifies the end of the primary theme. However, the transition that immediately follows also creates several emergent timbres through doubling across instrumental families. Starting at m. 13, the celli and basses begin the bass line with the augmentation of the countermelody mentioned earlier. They are soon joined by the trombone and bassoon in m. 18, adding complexity to the sound of the lower strings. Additional doublings occur between the upper strings and woodwinds, as well as the horns and brass, creating four blocks of related yet distinct melodic streams. Pajaro also used the timbral emergence phenomenon as a means of punctuating the end of a phrase. An example of this is with the X motive starting in m. 77, signifying the arrival of the medial caesura. The X motive gets repeated seven times over ten measures, with every 2-3 repetitions adding on an additional instrument. The X motive keeps growing and expanding in sound until m. 87, when the entire orchestra repeats the motive one final time. This final iteration is also the first time the entire orchestra is playing all at once. It seems as if Pajaro saves all-orchestra unisons for significant structural moments, since the only other time this occurs is during the final cadence of the closing theme in m. 121.

To visualize the changes in orchestration throughout the exposition, I created an orchestration graph modeled after Emily Dolan’s graphs in The Orchestral Revolution. Through this analysis, it became clear that each formal section is defined by the start of an instrumental solo, such as the opening low strings solo in the Primary Theme, flute solo in the Secondary Theme, and brass duet in the closing theme. Timbral emergence then acts as closing material, Together, those two extreme contrasts clarify the starts and ends of each section within the exposition.

Orchestration graph for the exposition of Philippine Symphony

Before reading through the score in the Eastman archives, I assumed that Pajaro used traditional Filipino instruments in the Philippine Symphony, similar to how Lucrecia Kasilag orchestrated her works. Finding that the symphony consisted of standard western orchestral instruments caused me to reconsider the story that I wanted to tell in this paper. I think this paper was a fruitful exercise in challenging assumptions. I initially conceived of the introduction of Western music theory and composition in the Philippines as solely a tool for colonialism, suppressing the voices of Filipino musicians. There is truth to that; the United States and the Philippines were in a relationship of unequal power dynamics, with the United States extracting land and resources from the Philippines in addition to imposing an education system from a place of paternalism. However, it is still important to remember that Filipino musicians were able to find their own voice even amongst the restructuring of education and the arts in the early 20th century. For Pajaro, this meant composing in a compositional style that hybridized his two main education institutions: the UP Conservatory and the Eastman School of Music. Pajaro achieved this in his doctoral dissertation by drawing upon but manipulating traditional forms and harmonies taught at the UP Conservatory, while also adhering to orchestration principles taught by Bernard Rogers. Perhaps it was Eastman, then, that served as his launching point to promote Filipino music and composers over the rest of his career. Of course, there is still much work to be done on this project; there’s more of the first movement to cover, after all. There’s also more to his life that we don’t know, for the only documentation is in the Philippines. What I hope this paper does is spark interest in Eliseo Pajaro’s music and encourage others to study the music and lives of Filipino composers.

Bibliography

A note on citations: this essay uses hyperlinks, rather than parenthetical or footnote citations, following the style guidelines of AMS Musicology Now. This practice is followed for ease of reading and to encourage interactivty with other sources.

Secondary Sources

Castro, Christi-Anne. Musical Renderings of the Philippine Nation. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Chapman, Abraham. “American Policy in the Philippines.” Far Eastern Survey 15, no. 11 (1946): 164-169.

Dolan, Emily. The Orchestral Revolution: Haydn and the Technologies of Timbre. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Grant, Roger Mathew. “Colonial Galant: Three Analytical Perspectives from the Chiquitano Missions.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 75, no. 1 (2022): 129-162.

Hepokoski, James, and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Hepokoski, James, and Warren Darcy. “The Medial Caesura and Its Role in the Eighteenth-Century Sonata Exposition.” Music Theory Spectrum, 19, no. 2 (1997): 115-154.

Kasilag, Lucrecia R. “Pajaro, Eliseo (Morales).” In Grove Music Online. Accessed November 12, 2025, https://doi-org.ezp.lib.rochester.edu/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.20723.

McAdams, Stephen, Meghan Goodchild, and Kit Soden. “A Taxonomy of Orchestral Grouping Effects Derived from Principles of Auditory Perception.” Music Theory Online 28, no. 3 (2022).

Mojares, Resil B. “The Formation of Filipino Nationality Under U.S. Colonial Rule.” Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 34, no. 1 (2006): 11-32.

Ocampo, Anthony Christian. The Latinos of Asia: How Filipino Americans Break the Rules of Race. Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2016.

Onorato, Michael Paul. “United States Influences in the Philippines.” Journal of Third World Studies 4, no. 2 (1987): 22-26.

Pajaro, Eliseo M. The Filipino Composer and His Role in the New Society. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 1973.

Richards, Mark. “Beethoven and the Obscured Medial Caesura.” Music Theory Spectrum 35, no. 2 (2013): 166-193.

Rogers, Bernard. The Art of Orchestration: Principles of Tone in Modern Scoring. New York: Appleton Century Crofts, 1951.

Samson, Helen F. Contemporary Filipino Composers: Biographical Interviews. Quezon City: Manlapaz Publishing Company, 1976.

Santos, Ramon P. “Art Music Form.” National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Accessed October 28, 2025. https://ncca.gov.ph/about-ncca-3/subcommissions/subcommission-on-the-arts-sca/music/art-music-form/

Santos, Ramon P. “Contemporary Music.” National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Accessed October 28, 2025. https://ncca.gov.ph/about-ncca-3/subcommissions/subcommission-on-the-arts-sca/music/contemporary-music/

Santos, Ramon P. “In Focus: Revivalism and Modernism in the Musics of Post-Colonial Asia.” National Commission for Culture and the Arts. December 29, 2003. Accessed October 28, 2025. https://ncca.gov.ph//about-culture-and-arts/in-focus/

Santos, Ramon Pagayon. Tunugan: Four Essays on Filipino Music. Quezon City: The University of the Philippines Press, 2005.

Primary Sources

Newspapers

Cover page to Eliseo Pajaro’s Philippine Symphony

Source: Sibley Music Library Special Collections

Eliseo Pajaro, interview by Howard Hanson. Howard Hanson Collection, Box 5, Folder 20. Eastman School of Music Special Collections.

Pajaro, Eliseo. The life of Lam-ang: A legend for orchestra based on an epic poem from the Philippines. Sibley Music Library Eastman School Archives, Eastman School of Music, 1951.

Pajaro, Eliseo. Philippine Symphony, in three movements. Sibley Music Library Eastman School Archives, Eastman School of Music, 1953.

“Symposium of Student Works for Orchestra By Members of Composition Classes of Wayne Barlow, Howard Hanson, Bernard Rogers.” Eastman concert program for the 1951-52 season. Eastman School of Music, 1952.

Democrat and Chronicle, Rochester, NY, April 15, 1951, newspapers.com.

Democrat and Chronicle, Rochester, NY, March 25, 1952, newspapers.com.

Democrat and Chronicle, Rochester, NY, October 2, 1955, newspapers.com.

Democrat and Chronicle, Rochester NY, December 25, 1963, newspapers.com.

The Chicago Defender, Chicago, IL, August 17, 1963, newspapers.com.

The News Journal, Wilmington, DE, July 16, 1951, newspapers.com.

The Tribune, Manila, Philippines, November 11, 1933, newspapers.com.

The Tribune, Manila, Philippines, July 16, 1936, newspapers.com.

The Tribune, Manila, Philippines, August 9, 1936, newspapers.com.

The Tribune, Manila, Philippines, November 28, 1937, newspapers.com.

The Tribune, Manila, Philippines, May 19, 1942, newspapers.com.